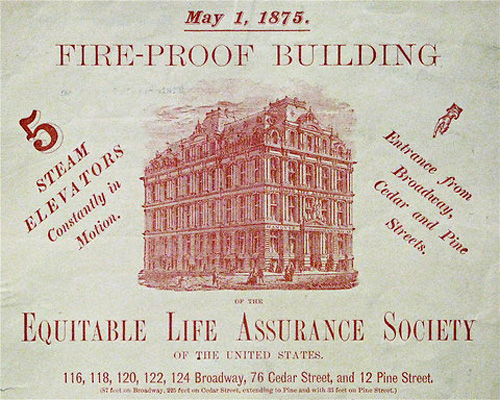

The building that changed New York City’s zoning laws began with grand but completely unrelated aspirations. When it was constructed in 1870 from a design by Gilman & Kendall and George B. Post, the Equitable Life Assurance Agency headquarters at 120 Broadway was considered a major breakthrough in the development of the skyscraper because of its skeletal steel frame, lightweight fireproof construction, and passenger elevators, a first in an office building. And still that wasn’t enough for Equitable’s president, who revealed plans to demolish the building in 1909. He wanted a building that would “establish in the public mind” a stronger impression of the company and its operations, according to a Landmarks Preservation Commission report, and use further advances in skyscraper construction to create an iconic structure akin to Ernest Flagg’s Singer Building, the tallest building in the world when it was completed in 1908.

With this concept in mind, Equitable hired Daniel Burnham, considered the “father of city planning” and a major proponent of the Beaux Arts style, to design their new headquarters. Burnham was asked to come up with a tower that would not only exceed the height of the Singer Building, but also exceed the proposed heights of the yet-to-be-built Metropolitan Life Tower (1909) and Woolworth Building (1913). However, Burnham’s plans never came to fruition. On January 9, 1912, the building lauded as the “city’s first skyscraper” was destroyed by a fire that couldn’t be properly contained due to the freezing weather. “[Ice] settled over the building in a gleaming sheath of white that made the fire a wonderful thing to see,” the Times wrote. “Ice converted the ruined building into a fantastic palace, with the rainbows arching at every turn as the sunlight filtered through the spray and smoke.” Six men perished within this “fireproof” building. Although the building was decimated, Equitable remained afloat because their records were stored off-site and their vault survived the blaze.

With this concept in mind, Equitable hired Daniel Burnham, considered the “father of city planning” and a major proponent of the Beaux Arts style, to design their new headquarters. Burnham was asked to come up with a tower that would not only exceed the height of the Singer Building, but also exceed the proposed heights of the yet-to-be-built Metropolitan Life Tower (1909) and Woolworth Building (1913). However, Burnham’s plans never came to fruition. On January 9, 1912, the building lauded as the “city’s first skyscraper” was destroyed by a fire that couldn’t be properly contained due to the freezing weather. “[Ice] settled over the building in a gleaming sheath of white that made the fire a wonderful thing to see,” the Times wrote. “Ice converted the ruined building into a fantastic palace, with the rainbows arching at every turn as the sunlight filtered through the spray and smoke.” Six men perished within this “fireproof” building. Although the building was decimated, Equitable remained afloat because their records were stored off-site and their vault survived the blaze.

After the fire, Equitable’s president was wary of erecting a tower that could succumb to a similar fate and vowed never to undertake an extravagant building project again, so Burnham’s plans were scrapped. Favoring a more economical approach, Equitable decided to design and build the largest building that could fit on the site to ensure the greatest profit from rentable space. Ernest R. Graham, who assisted with the 1893 World Columbian Exposition and the 1909 Plan of Chicago and had been Burnham’s partner for over a decade, was chosen as architect. As the company wanted a building that emphasized stature and solidity, Graham’s firm seemed a perfect choice; it had been lauded as effectively adapting the “Beaux-Arts classical styles to modern American buildings in a variant that has been called ‘commercial classicism’” as well as, in the words of the NYC Landmarks Designation report, “using Beaux-Arts planning principles to adapt enormous new structures to the American city and to define or reduce the urban context around them.”

After the fire, Equitable’s president was wary of erecting a tower that could succumb to a similar fate and vowed never to undertake an extravagant building project again, so Burnham’s plans were scrapped. Favoring a more economical approach, Equitable decided to design and build the largest building that could fit on the site to ensure the greatest profit from rentable space. Ernest R. Graham, who assisted with the 1893 World Columbian Exposition and the 1909 Plan of Chicago and had been Burnham’s partner for over a decade, was chosen as architect. As the company wanted a building that emphasized stature and solidity, Graham’s firm seemed a perfect choice; it had been lauded as effectively adapting the “Beaux-Arts classical styles to modern American buildings in a variant that has been called ‘commercial classicism’” as well as, in the words of the NYC Landmarks Designation report, “using Beaux-Arts planning principles to adapt enormous new structures to the American city and to define or reduce the urban context around them.”

The building, designed by Graham in conjunction with his associate Peirce Anderson, was certainly in keeping with their established reputation of “reducing the urban context” as they created a building that would become notorious for its massive size. The 38-story steel-frame building rose straight up from the street lot-line without any setbacks, thus making it the largest office building in the world with 1,200,000 square feet of rentable office space and the capacity to hold a daytime population of 16,000 office workers. Graham produced a mammoth building with state-of-the-art elevators, heating and ventilation systems and advanced fireproof construction. The Equitable Building’s 1914 brochure declared:

The building, designed by Graham in conjunction with his associate Peirce Anderson, was certainly in keeping with their established reputation of “reducing the urban context” as they created a building that would become notorious for its massive size. The 38-story steel-frame building rose straight up from the street lot-line without any setbacks, thus making it the largest office building in the world with 1,200,000 square feet of rentable office space and the capacity to hold a daytime population of 16,000 office workers. Graham produced a mammoth building with state-of-the-art elevators, heating and ventilation systems and advanced fireproof construction. The Equitable Building’s 1914 brochure declared:

“Equitable Building exhibits a felicitous combination of both utility and beauty. Economy has not encroached upon either external beauty or internal excellence. Its exterior is built of granite, brick and terra cotta in soft tones and is designed after the Italian Renaissance. In shape the Equitable Building simulates the letter H. Thus, its interior offices are interior in name only, and have nothing in common with the traditional darkness of average interiors. And the character of the construction throughout is as fine as mind and money can make it. It is beautiful, substantial and even luxurious, revealing fine craftsmanship in every detail of finish and design, and will rank as one of the really beautiful buildings on this continent.”

But the public did not feel similarly. In fact, disdain for the building began as soon as the initial plans were announced, as adjacent property owners began to fear that the new building would block sunlight from their offices. Fearful of the development, they presented two alternate proposals for the site—one for a public park and the other to subdivide the site into two smaller lots to facilitate the construction of smaller buildings. However, these alternatives never made it past the discussion phase, and the building was built as planned.

Not surprisingly, it did not take long before the Equitable became the “poster building” for the perils of unregulated development. Prior to the construction of the Equitable Building, no municipal code governed the height or bulk of buildings. However, the emergence of steel-frame construction and elevators enabled buildings to be built taller and larger, creating buildings of a size New York City had never experienced. There was discussion of regulating bulk and height long before the Equitable Building was constructed, but the building’s completion pushed the issue to the forefront. Sentiments such as the one quoted here from the NYC Landmarks Designation Report were commonplace:

Not surprisingly, it did not take long before the Equitable became the “poster building” for the perils of unregulated development. Prior to the construction of the Equitable Building, no municipal code governed the height or bulk of buildings. However, the emergence of steel-frame construction and elevators enabled buildings to be built taller and larger, creating buildings of a size New York City had never experienced. There was discussion of regulating bulk and height long before the Equitable Building was constructed, but the building’s completion pushed the issue to the forefront. Sentiments such as the one quoted here from the NYC Landmarks Designation Report were commonplace:

“It was said that the Equitable blocked ventilation, dumped 13,000 users onto nearby sidewalks, choked the local transit facilities, and created potential problems for firemen. The Equitable’s noon shadow, someone complained, enveloped six times its own area. Stretching almost a fifth of a mile, it cut off direct sunlight from the Broadway fronts of buildings as tall as 21 stories. The darkened area extended four blocks to the north. Most of the surrounding property owners claimed a loss of rental income because so much light and air had been deflected by the massive new building, and they filed for a reduction in the assessed valuations of their properties.”

Preceding the building’s construction, hearings and meetings were convened with the goal of creating an enforceable regulation that would prevent a building such as the one Equitable created from occurring again. Two prominent architects of the time spearheaded the effort for building regulation—Ernest Flagg, the architect of the Singer Building, proposed lot area restrictions, and D. Knickerbocker Boyd, the president of the Philadelphia Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, proposed building set-backs to permit light and air. Ultimately, these proposals were incorporated into the landmark 1916 Building Zone Resolution, which enforced the construction of “stepped façade” towers in the city’s business districts as well as the three- to six-story residential buildings found throughout New York City.

The 1916 Building Zone Resolution was the first comprehensive zoning regulation of its kind, and much like any New York City endeavor, it set the benchmark for other cities. Nationally, it set the precedent for the 1924 Standard State Zoning Enabling Act, which laid the basic foundation for planning and zoning within the United States. The Equitable Building, which was granted landmark status in 1996, will forever be the symbol of the results of unregulated building construction. Yet with all of the monstrous and ill-fitting high-rises that have been erected since zoning regulations have been in place, perhaps one of these will be the catalyst for the next phase of zoning and development controls—just as the Equitable Building was nearly 100 years ago.

Lisa Santoro

http://ny.curbed.com/archives/2013/03/15/the_equitable_building_and_the_birth_of_nyc_zoning_law.php

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.