This week, the New York Times ran an important series of articles on state and local incentives to business. The reporting was terrific, but even better is the data set the Times put together on the scale and scope of these incentives. The paper points out that its reporters spent some 10 months compiling data from states, cities, and counties.

This week, the New York Times ran an important series of articles on state and local incentives to business. The reporting was terrific, but even better is the data set the Times put together on the scale and scope of these incentives. The paper points out that its reporters spent some 10 months compiling data from states, cities, and counties.

All told, states, cities, and counties give away some $80 billion to companies each year, including both expenditures and tax abatements, according to the Times’ estimates. There are 48 companies which have received more than $100 million in incentives since 2007, led by General Motors, which took in a whopping $1.77 billion in incentives. Other companies that are part of the $100 million incentive club include: Ford, Chrysler, Daimler, General Electric, Shell, Dow, Amazon, Microsoft, IBM, Google, Caterpillar, Procter & Gamble, Sears, Boeing, Airbus, Panasonic, and Electrolux. More than 5,000 companies received one million dollars or more in incentives, according to the Times’ estimates.

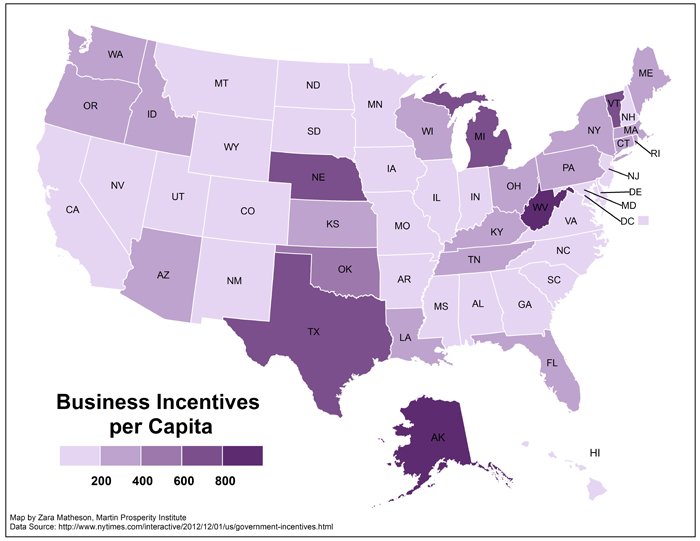

When it comes to states, Texas leads them all in these corporate giveaways, with $19.1 billion in outlays per year, more than 2.5 times the next highest state, Michigan, with $6.6 billion in annual giveaways. Pennsylvania is third with $4.8 billion, followed by California ($4.2 billion), New York ($4.1 billion), Florida ($3.98 billion), Ohio ($3.24), Washington ($2.35 billion), Massachusetts ($2.26), and Oklahoma ($2.19). All in all there are 21 states that grant more than one billion in incentives each year and another 10 that give between $500 million and a billion.

Even more interesting are the Times’ figures on incentive dollars per capita. The map (above), by the Martin Prosperity Institute’s Zara Matheson based on the Times data, shows economic development incentives per capita across the 50 states. Alaska leads, spending a whooping $991 on incentive spending per person each year. West Virginia is second at $845 per person, Nebraska third ($763), Texas fourth ($759), Michigan fifth ($672), and Vermont sixth ($650).

With the help of the MPI’s Charlotta Mellander, I examined to what degree these economic development incentives are related to state economic performance. Mellander ran correlations between economic development incentives per capita and economic variables like wages, income, poverty levels, education levels, knowledge workers, and so on. As usual, I note that correlation does not mean causation.

Our biggest takeaway: there is virtually no association between economic development incentives and any measure of economic performance. We found no statistically significant association between economic development incentives per capita and average wages or incomes; none between incentives and college grads or knowledge workers; and none between incentives and the state unemployment rate. The scatter-graph above illustrates the lack of any relationship between incentives per capita and wages.

The only statistically significant association we find is between incentives and the poverty rate. This is in line with other research by Robert Greenbaum and Daniele Bondonio, which finds economic development incentives to be more likely in poorer, more economically disadvantaged communities, especially those that have faced recent economic decline.

Our findings are consistent with the broad body of research on incentives. A detailed 2002 study, published in the Journal of Regional Science [PDF] of more than 350 companies that received incentives, found incentives had a negative effect on these companies’s ability to create jobs. Using detailed statistical models to control for a wide variety of factors, the study found that companies that received incentives expanded more slowly than others, and worse yet that overall effect of incentives was a reduction of 10.5 jobs per establishment. Incentives had their biggest effect by far not on actual jobs, but on “announced growth,” finding that the average business receiving incentives overestimated its future employment by 28.5 jobs.

There is one study that suggests incentives can sometimes play a positive role. Conducted by economists at MIT and the University of California, Berkeley, it examined the effects of “million dollar” manufacturing plants on community economies, and found that such locational choices led to small increases in wages, productivity, and property values compared with other similar locations. These findings are not too surprising given the focus on large plants in mainly small communities. The study suggests that its results “undermine the popular view that the provision of local subsides to attract large industrial plants reduces local residents’ welfare,” but qualifies this with several caveats:

he bigger issue is that incentives do little to alter the locational calculus of most companies. The broad body of evidence on incentives, including the Times series, finds that incentives do not actually cause companies to choose certain locations over others. Rather, companies typically select locations based on factors such as workforce, proximity to markets, and access to qualified suppliers, and then pit jurisdictions against one another to extract tax benefits and other incentives.

A 2011 Lincoln Institute of Land Policy study found property tax incentives to be counterproductive, being all too frequently given to companies that would have chosen the same location anyway. So instead of creating new jobs or spurring employment, the main effect of incentives is simply to deplete a community’s tax base. Since poorer states and communities are more likely to use incentives in the first place, the end result is to undermine the resources and revenues of the places that can least afford it.

And, a 2012 report by the Pew Center on the States found that most states that offer incentives do not have effective mechanisms in place to gauge and evaluate them, concluding that fully half of all states do not have even the most basic provisions in place to know whether the incentives they give are in any way effective.

The Times should be commended for compiling such detailed data and shining a public light on this incredible economic development boondoggle. We can only hope it helps put an end to this long-standing waste of state and local resources.

Lede image: General Motors Headquarters in Detroit, Michigan on Nov. 3, 2009. (Rebecca Cook/Reuters)

Keywords: Maps, Incentives, Job Growth

Richard Florida is Co-Founder and Editor at Large at The Atlantic Cities. He’s also a Senior Editor at The Atlantic, Director of the Martin Prosperity Institute at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, and Global Research Professor at New York University. He is a frequent speaker to communities, business and professional organizations, and founder of the Creative Class Group, whose current client list can be found here. All posts »

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.